Hi Everyone! Happy Holidays. This piece was written with Lea Boreland, the mastermind behind Four Layers, a newsletter designed for people who want to move past unexplanatory theses and learn about a new industry from scratch. Today’s newsletter builds on last month’s exploration, The Promise of Stripe Press.

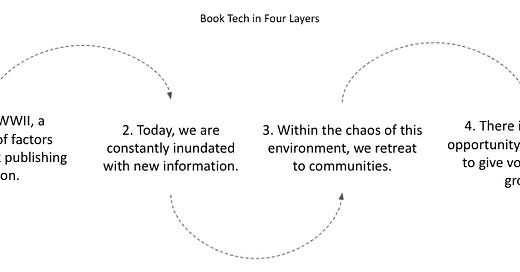

Lea and I set out to discover the role of a book in the current information environment. We’ll argue that in an environment predicated upon immediacy, books win by being slow and thoughtful. As we’re inundated by new contributors - internet cults, Substack writers, Twitter influencers - the book publishing industry can win by giving formal, material validation to the voices in these online spaces.

We’ll trace the history of book publishing since WWII and argue that the information environment today is driving the online population to seek digital communities. Let’s dive in!

I. Around WWII, a confluence of factors created a book-publishing explosion.

In the early 1900s, books (mainly printed as hardcovers) were expensive for the average person. During the Great Depression, Penguin was the first publisher to try an alternate tactic aimed at the masses: the paperback book.

Over the course of World War II, over 120 million paperback books were printed and delivered to soldiers, and this drove a broad cultural appetite for books in subsequent decades (The Atlantic). These books, called “Armed Services Editions,” were distributed widely. They embodied an ethos in direct opposition to the censorship displayed by the Axis powers.

A group of publishers and authors formed the Council on Books in Wartime to position books as "weapons in the war of ideas,” according to the Philadelphia Area Archives Research Portal. The Council on Books in Wartime also helped popularize paperbacks. The Wall Street Journal aptly summarized the impact of the Council: “The program...provided the foundation for the mass-market paperback,” said Michael Hackenberg, a bookseller and historian. “It also turned a generation of young men into lifelong readers.”

Post-war policy and lifestyle changes then formalized the position of the book at the center of the American entertainment menu. This article by Rich Rennicks put it best: “Reading a book ceased to seem like a difficult or dull task, and when the GI Bill made a college education available for many, a generation of men were ready to take advantage -- growing the middle class, and making the post-war consumer boom possible.” As soldiers returned from war and purchased suburban homes, built-in bookshelves were also offered as a standard option for the first time, creating the physical space for a reading habit.

Lastly, innovations to the book manufacturing process (ex., the invention of the photocomposition process) reduced input costs, making it easier to support burgeoning demand.

II. Today, there are a zillion books, and we are constantly inundated with information.

More than one million books are self published each year—in addition to a few hundred thousand that go to market via the traditional publishing route. As one publishing house writes, “No other industry has so many new product introductions. Every new book is a new product, needing to be acquired, developed, reworked, designed, produced, named, manufactured, packaged, priced, introduced, marketed, warehoused, and sold. Yet the average new book generates only $50,000 to $100,000 in sales…”

Amidst this soaring supply, industry revenue has been stagnant. A book competes for your attention not just with the other 130 million books out in the universe, but (to paraphrase Netflix CEO Reed Hastings) with every other entertainment option out there, from Fortnite to HBO to sleep. This results in a universe wherein the average American between 15 and 44 reads, on average, for 10 minutes or less per day.

III. Within the chaos of this environment, we retreat to communities.

The difficulty of this environment has less to do with the sheer quantity of information that we must sift through, and more to do with the number of voices producing it. There is no master adjudicator of perspectives on the internet; instead our interests, powered by whatever internet discovery heuristics we’ve cobbled together, navigate us to information faucets like these that we feel we can trust. We come to identify with those faucets as a matter of identity, and communities form around them. We have personal twitter kings and podcast gods.

In the tech Twitter sphere, there is Naval and Jack Butcher and Paul Graham and David Perell, to name a few. A software called Roam has produced a tribe called Roamians. These kings and the communities that surround them help us to weather the world of rogue voices, equal parts terrifying and delightful, that the internet has become.

So twenty years after Robert Putnam first said that Americans are doing too much bowling alone, the chaos of the internet has given us the impetus to form bonds again. What we’re seeing is like a mini rebirth of tribalism: a flip-flop back toward the protections of visceral community.

The interesting and meritocratic part of this is that the people who become information kings on the internet do so not because they control manufacturing and distribution (ex., NYT,) but because people like their ideas. This necessarily becomes a problem for the institutions that are popular not based on the merits of their information coverage but the economics of their distribution.

The opportune thing for those institutions is that the niche and novel content produced by those communities is highly monetizable. A few weeks ago Ben Thompson wrote about this in The Idea Adoption Curve:

What these maps are saying is that while more people watch the evening news than read the latest greatest academic paper, the ideas that inform the evening news often come from those academic papers and journals. And increasingly, the ideas will come from podcasts and newsletters and tweets and blogs, produced and written by Twitter kings, consumed by their surrounding communities. As Thompson himself proves, people are more willing to pay for the sliver of exciting, strange, novel content that truly speaks to their experience and interests, than they are willing to pay for large-scale, generic media.

IV. There is a massive opportunity for book publishers to give voice to these groups - if they can create the business models to do so.

There is an opportunity for publishers to focus on giving voice to the new and echoing communities at the beginning of the idea curve. The communities usually live on the internet, which means they live in ephemeral mediums: tweets, fleets, and newsletters that get buried at the bottom of your inbox. There is something to be said about apotheosizing the truths of those communities that are written in disappearing mediums into the sturdy, old-fashioned, hold-it-in-your-hand object of a book.

A company that writes the book (haha) on how to do this is Stripe Press, a media arm of the software provider Stripe. Stripe Press’s books, like Working in Public and Revolt of the Public formalize the musings of internet tech communities into the time-treasured form and structure of a book. The books are always beautifully-bound and artistically-designed hard covers: they’re not building paperbacks, they’re building relics and heirlooms. This is a reversal (or, perhaps more accurately, a continuation) of the paperback trend ushered in during WWII.

Other case studies are the also-beautiful Farnam Street Mental Models collection and the Twitter-famousAlmanack of Naval, the latter of which is powered by and targeted to the aforementioned Naval cult.

Evidence of success exists for community-propelled publishing; the challenge is economics. The examples we’ve shown don’t look like a traditional publishing house: Stripe Press is effectively a grown-up content marketing arm, conceivably without its own P&L responsibility. The Almanack of Naval is given away for free. Farnam Street first only released their books to a paid-only online community.

Distribution of community-propelled books would be lower by nature, but the unit price could be enormously higher. Thompson shows this above: willingness to pay is right-skewed against the idea curve. Whether this is enough to offset production costs depends on the community and should inform the shape of the final product (ex., ebook vs hardcover).

In sum, traditional publishers are going to need to get creative with their business models if they want to play ball in this universe, and if they do, the opportunity to build physical relics on the back of digital communities is huge. The modern publisher is tempted to compete with the limited attention spans born from the relentless news cycle, but there is a larger and still-untapped opportunity afoot. Publishers are presented with the opportunity to provide unique, intriguing, niche content that speaks to communities. Publishers need to select authors who transcend the aggression of the news cycle and have digital zealots. They need authors who can synthesize global news and events, but identify themes that transcend news, and deliver information with wit and personality. This drives the cycle of reader loyalty, and reinforces the need for publishers to maniacally focus on the relationship the reader has with the author.

Thank you to Thad McIlroy for providing key input and insights!

Related Reading:

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak - Morgan’s favorite book (and movie)

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara - Lea’s favorite book

Thanks for reading, and please reach out if you have any feedback!